Table of Contents Show

Roger Federer delivered a commencement speech at Dartmouth University this past summer, sharing a profound insight from his tennis career that equally applies to other walks of life.

He mentioned that he played 1,526 singles matches during his career, winning nearly 80% of them. But then he posed a question to the graduating class:

“Now I have a question for all of you. What percentage of the points do you think I won in those matches?”

The answer? 54%.

Despite being one of the greatest tennis players ever, Federer won barely more than half the points available to him. The magic came from a small, consistent edge that compounded into something extraordinary over time.

Investing works much the same way.

Day-to-day market movements are unpredictable. Whether the stock market is positive or negative on any single day is basically a coin flip, with a modest edge to positive return days at 53% of the time.

That doesn’t seem like much, but like Federer, this razor-thin edge can compound into something great. However, it requires discipline—something Federer initially struggled with. As he explained:

“The wake-up call came early in my career when an opponent at the Italian Open publicly questioned my mental discipline. He said, ‘Roger will be the favorite for the first two hours, then I’ll be the favorite after that.’”

Federer struggled to stay consistent for an entire match—he started fast and finished slow. In short, his discipline faded as he got tired.

Investors don’t have to venture far for the analogy. Everyone feels like a great investor during a bull market, but the real test comes when times get tough. Federer became intensely focused on improving his competitive process, which included more cardio and analyzing data to exploit opponent weaknesses. He remained committed to this process for the rest of his career.

Each part of his discipline compounded to make him one of the greatest players ever. Intense cardio work led him to staying sharper later in matches. Being sharper later in matches allowed him to take advantage of opponent weaknesses. Combined, these two factors forged a foundation of self-belief.

Federer remarked that, “Belief in yourself has to be earned. [And there came a moment] when my self-belief really kicked in.”

The question becomes: Is there a similar flywheel that investors can implement, which compounds over time and potentially provides that slight edge? There are few key building blocks worth mentioning:

Building Block #1: Costs Matter

The only guarantee in the investment business is that you will keep more if you spend less.

John Bogle referred to this as the Cost Matters Hypothesis. It’s simple subtraction—the costs incurred investing (fund fees, transaction fees, management fees, and so on) are deducted directly from returns.

Prudent investors should choose investments with this concept in mind. Does that mean buy only low-fee funds? No. Rather, the hurdle for high-fee funds must be higher than lower-fee options.

Building Block #2: Manager Selection

Pairing cost discipline with diligent manager selection is crucial.

Like Federer, investment strategies and asset classes will always be subject to periods of short-term underperformance.

Investment strategies and asset classes will always be subject to periods of underperformance. Some investors might waive the proverbial flag in these situations and seek opportunities elsewhere. While it’s situation-specific, a disciplined approach would be to understand long-term investment trends and use periods of pessimism to allocate to underperforming managers or asset classes.

Building Block #3: Global Diversification

Diversifying globally helps mitigate blind spots. The next 10 years will likely differ from the past decade, a simple but crucial reminder of why diversification is essential.

This year, China and Argentina have been the top-performing global equity markets—an outcome that nobody predicted. While the US has led global equities over the past decade, the 10 years prior (2000–10) saw US stocks return 0%.

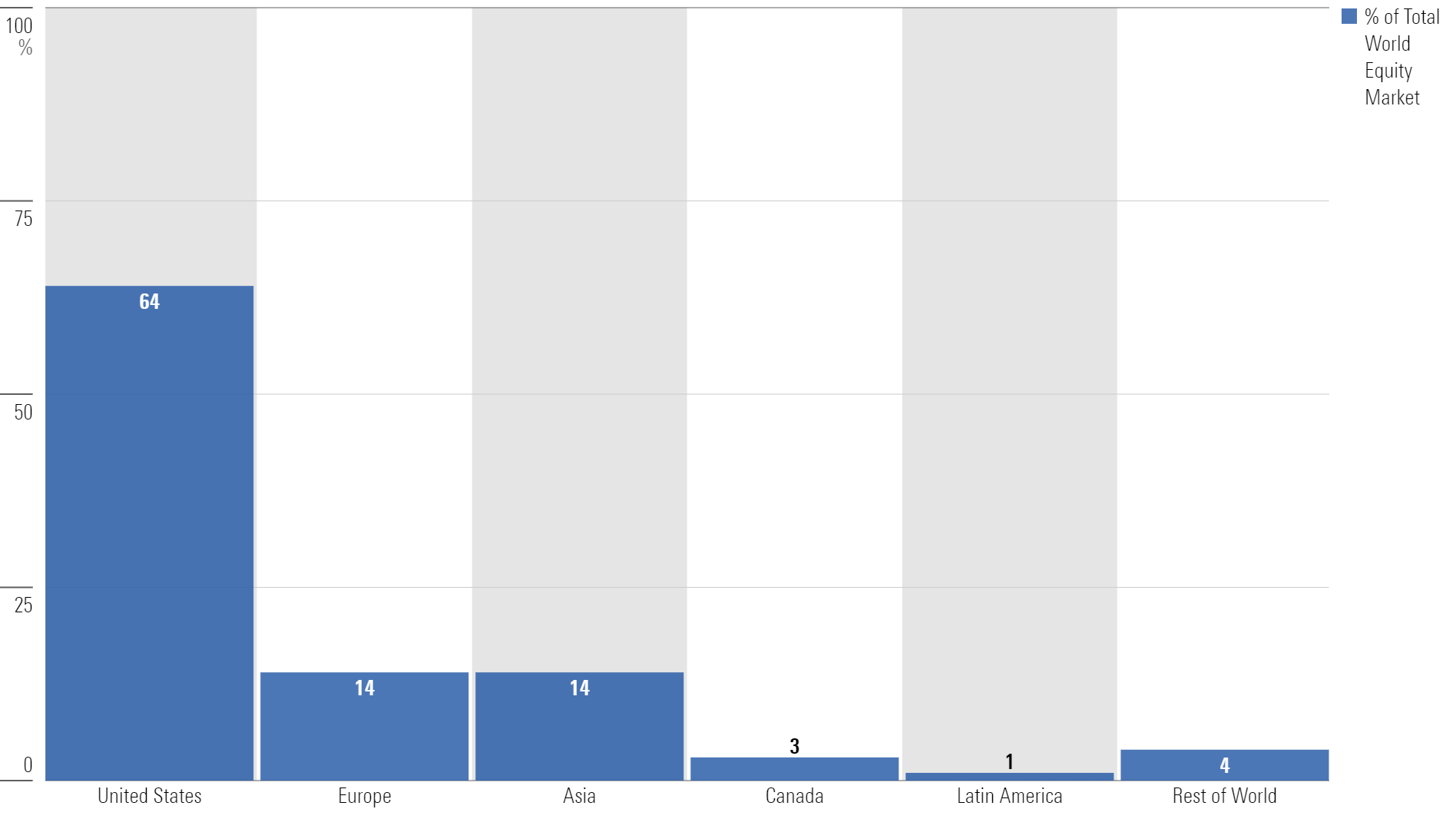

Given that the US represents 60% of the world’s market capitalization, it should be a significant part of any portfolio.

Ideally, investors should want to “fish where the fish are,” meaning they shouldn’t isolate themselves to one corner of the lake. That’s why it’s important to think globally when investing.

Building Block #4: Rebalancing

Burton Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, once wrote:

“We all wish some genie could tell us when the stock market tops out so we could sell. Rebalancing is the closest technique available to do that.”

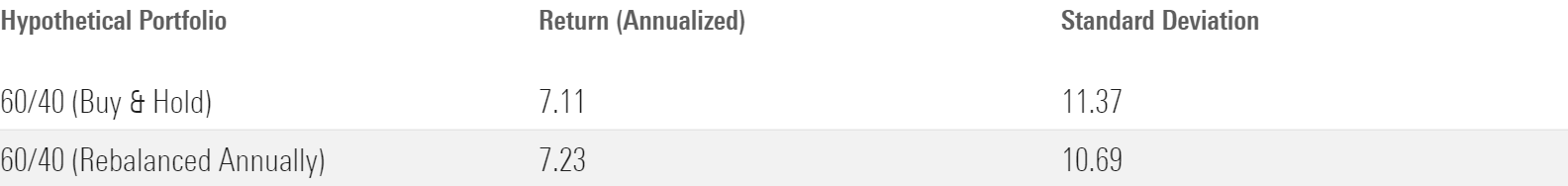

As an example, a hypothetical 60% global equity/40% US bond portfolio rebalanced annually over the past 30 years outperforms a buy-and-hold portfolio with less volatility over time.

Building More Resilient Portfolios

The goal is for each building block to build upon the last, creating a more disciplined process. Ultimately, this should lead to more resilient portfolios and potentially more durable investment outcomes.

This process alone promises nothing; perfection will never be attainable. However, it strengthens discipline and can potentially unlock the short-term edge that, over time, compounds into meaningful success.

Federer went on to add that, “Most of the time, it’s not about having a gift, it’s about having grit.”

In any walk of life, there are ways to take advantage of compounding over time—an investment process should be no different.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.