Table of Contents Show

Unlocking Climate Finance for Least Developed Countries: Innovations and Opportunities

The climate finance gap for least developed countries is well-documented, but practical ways to close it remain limited.

Least-developed countries (LDCs) are among those most exposed to intensifying climate risks, despite contributing the least to climate change. Challenges related to economic stability, fiscal space, and policy environments often hinder their ability to attract climate investment or respond to disasters.

Even as public development finance institutions (DFIs) ramp up adaptation finance for climate-vulnerable nations, countries with the least adaptive capacity receive less than those better equipped to respond. Just 11% of total adaptation finance tracked to Africa in 2022 went to the 10 most climate-vulnerable countries, as ranked by ND-GAIN. In terms of emissions abatement, LDCs received just 1% of global mitigation finance in 2022.

As climate funders and countries prepare for the UN’s Fourth International Conference on Finance for Development (FFD4) in Seville, it is timely to consider three underexamined aspects of climate finance in LDCs:

1. How are LDCs piloting climate solutions and financial innovations to manage their risks?

2. Why do current climate finance mechanisms not always meet LDC needs?

3. How can different public actors play their part in facilitating fit-for-purpose climate finance in these countries?

1: LDCs as Innovators on Climate Action

Long exposed to heightened climate risk, LDCs have been forced to innovate to build resilience. For instance, Bangladesh—one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries due to its low-lying delta geography—has drastically improved its resilience to cyclones over time. While Cyclone Bhola caused almost half a million deaths in 1970, similar storm surges from Super Cyclone Amphan saw just 26 deaths in 2020, with fatalities avoided by early warning systems, cyclone shelters, and community training. The sharp drop illustrates how national and local leadership, combined with long-term investment in disaster preparedness, can save lives.

Nevertheless, the devastating economic losses caused by Amphan across the subcontinent demonstrate the need to pair climate risk investment with innovative financial instruments that also bolster economic and livelihood resilience in LDCs.

The two examples below demonstrate how context-specific instruments can help close the climate finance gap.

Parametric protection through ARC

LDCs require more support to ensure that climate disasters do not overwhelm already-stretched public budgets. When extreme weather events strike, emergency spending further constrains fiscal space, exacerbating debt and human suffering.

The Africa Risk Capacity Group (ARC) provides rapid financing to support response, recovery, and reconstruction following climate-related disasters. The sovereign risk pool, facilitated through the African Union and ARC Insurance Company Limited (ARC Ltd.), finances relief via parametric insurance in member countries, most of which are LDCs. When certain climate conditions are met, payouts are released.

For example, in 2022, ARC Ltd. and the African Development Bank released USD 5.37 million to Zambia, where prolonged drought had led to widespread food insecurity. Subsequent government electronic cash transfers to farmers enabled them to diversify and increase their incomes, including by launching small livestock businesses.

Donor capital is crucial to maintaining affordable and timely coverage by ARC. Alongside the commitments of African governments and regional/local financial institutions that drive ARC’s uptake, the UK and Germany have committed long-term, interest-free financing of GBP 30 million and USD 48 million, respectively. This support has helped ARC Ltd. to maintain an A- Long Term Insurer Financial Strength rating from Fitch, keeping premiums affordable for member countries, maintaining solvency, and nearing its goal of scaling to a USD 100 million insurance company.

ARC demonstrates how donor capitalization can enable climate insurers to serve in high-risk, low-resource settings. By injecting patient capital into sovereign risk pools, donors can help LDCs manage climate shocks proactively—opening fiscal space, improving the timeliness of disaster response, and protecting lives and livelihoods.

Clean energy meets peacebuilding via P-REC

Support is also vital where climate vulnerability overlaps with chronic energy poverty and conflict risk. Of the 800 million people who lack access to electricity globally, 80% live in fragile, conflict-prone states. These compounding vulnerabilities make it difficult to finance the energy infrastructure needed for sustainable development.

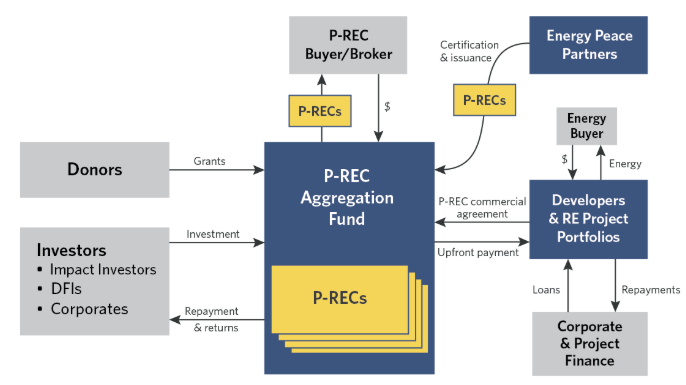

The Peace Renewable Energy Credit (P-REC) Aggregation Facility addresses this challenge by channeling revenue to clean energy projects in conflict-affected countries. Like standard renewable energy credits, each P-REC represents 1 MWh of clean energy, but is uniquely issued for first-time electrification projects in conflict-affected areas. Developers can sell these credits to corporate buyers seeking to offset their emissions, creating an additional revenue stream.

The P-REC Aggregation Facility uses the Positive Peace Framework to track improvements in community stability and resilience. For example, sales of P-RECs from a 1.3 MW solar mini-grid in Goma, DRC, funded community streetlights and electrification. These investments were linked to improvements in local Sustainable Development Goal indicators and residents’ safety perceptions, while supporting job creation, improved reliability of health and education services, and opportunities for cooperation and peacebuilding.

The P-REC facility was funded by eight philanthropies, supporting early instrument development and helping broker partnerships with corporate buyers, including Google, Microsoft, and Coca-Cola. Linking corporate climate commitments with investment in hard-to-reach markets is critical for replicating and scaling the impact of smaller interventions.

CPI and its partners worked through the Global Innovation Lab for Climate Finance and the Catalytic Climate Finance Facility to support the development of the P-REC, which is designed as follows:

By de-risking early investments, philanthropies circumvented weak enabling environments and high perceived risks to scale P-RECs in LDCs, bringing corporate finance to meet community energy needs.

While the examples above showcase context-specific innovation, many current climate finance approaches are ill-suited to LDCs’ macroeconomic and institutional realities.

2. Why current climate finance fails LDCs

The international financial architecture must be reshaped to tailor climate finance to address LDCs’ constraints, rather than following approaches used in more developed economies. Climate finance for LDCs should prioritize grant-based and concessional resources that avoid deepening debt distress.

Cross-border climate finance mechanisms that depend on debt often assume stable macroeconomic environments, predictable regulatory regimes, and the presence of financial intermediaries—conditions that are rarely present in LDCs.

LDCs face similar—but more acute—challenges to those of more developed emerging markets. These include:

- Limited fiscal space: Many LDCs are debt-distressed and cannot take on additional borrowing. This may prohibit debt mechanisms commonly deployed to finance climate projects, due to cost or future economic impacts.

- Weak enabling environments: Climate finance mechanisms predicated on strong policy environments or monitoring and evaluation capacity (e.g., debt-for-climate swaps, outcome-contingent payments, and catastrophe bonds) may not be viable in many LDCs.

- Currency risk: Where opportunities for climate lending exist, significant foreign exchange (FX) risk elevates LDCs’ borrowing costs and exposes them to currency fluctuations that exacerbate debt burdens from foreign lenders.

- Project-level concerns: Small transaction sizes, limited pipelines, and the perceived lack of bankability of LDC climate projects prohibit developers from attracting investment.

Given these challenges, LDCs cannot rely on the current suite of debt-focused international climate finance mechanisms, which require market and institutional capacity. Strengthening domestic markets and institutions remains a critical long-term goal; however, climate finance must meet the needs of LDCs as they currently stand, prioritizing urgent adaptation and resilience requirements. In practice, this means highly concessional—ideally, grant-based—finance.

It is appropriate that some of this support resembles humanitarian or development aid. LDCs’ climate and development outcomes are deeply interconnected, and disentangling the two is neither practical nor beneficial.

3. The role of highly concessional finance providers

Different public actors can play diverse roles in increasing climate finance for LDCs. Philanthropies, non-profits, and donor governments can deploy flexible, non-return-seeking capital, while DFIs can deploy low- or no-interest loans to complement domestic government priorities.

The table below captures the key roles and comparative advantages for each institution type:

| Institution Type | Core functions | Distinct role in supporting LDCs |

|---|---|---|

The Path Forward

For climate finance to be just and effective, those with the fewest resources and greatest need must be prioritized. LDCs are already driving innovation in climate policy and finance, but closing their climate investment gap will require deliberate and coordinated action.

National efforts must be complemented by systemic reforms and scaled up through international support. Instead of debt, donor governments, philanthropies, and DFIs should prioritize channeling grant-based or highly concessional capital to fit-for-purpose climate finance instruments that absorb risk and build local capacity.

As leaders prepare for FFD4, they must turn to action—building a more inclusive climate finance system that works for LDCs. The opportunity to advance the goals of the Bridgetown Initiative and shape a more inclusive international financial architecture is clear, and the tools already exist.

Doing so will require a focus on leveraging capital that is catalytic, concessional, and context-specific—making sure that the most vulnerable are not left behind.

Note: A list of least-developed countries can be found here: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/list-ldcs