Table of Contents Show

Everyone is looking for “the next lithium” in reference to the massive rallies ASX listed lithium stocks have enjoyed over the last 24 months. Some have bravely touted uranium as the next resources sector destined to pop.

Clearly there are some key potential drivers here, energy security concerns in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and longer term, the necessary and impending switch away from fossil fuels. Uranium (which powers nuclear power stations if you didn’t know!) is sensibly mentioned as a solution to both of these pressing issues.

But “common sense” and a “plausible story” doesn’t always translate into profits for your portfolio. For as long as stocks have been around, plausible stories have caused investors to hold onto stocks which aim to capitalise on a plausible story – despite the absence of any eventual real-world economic traction, and worse still, any eventual stock price appreciation!

So, is uranium going to be the next big thing? This article aims to address this question. It’s part one of a two-part series in which we take an unbiased look at each of the key factors driving both the demand and supply side of the uranium market. In Part 2, which we will publish next week, we will look at each of the key ASX listed uranium stocks. There are 30 on the list, ranging from those on the verge of production, to those still kicking over rocks in the desert – so stay tuned!

Highlights:

- Uranium Market Demand Side

- Uranium Market Supply Side

- Sprott Physical Uranium Trust

- Uranium Price Outlook

Uranium market demand side

Due to its inherent properties as a radioactive material, uranium has limited applications compared to many other industrial metals. It is primarily used in the electricity generation industry, but it is also used in defence, and various isotopes of uranium are used by the medical industry to sterilise medical equipment.

By far however, the greatest consumption of uranium globally is a result of energy production. Nuclear reactors convert uranium into electricity, delivering a (generally accepted) safe and reliable baseload. Nuclear power as it is commonly referred to, is generally a lower cost alternative to other sources of energy, and it is (generally accepted) a more environmentally friendly option than traditional carbon-based options. Some of these comments are contentious, and I have no desire to investigate the arguments one way or the other further! Regardless of your politics, the consensus is nuclear power will play a major role (alongside renewables) in facilitating the world’s march to carbon neutrality. Certainly, nuclear power appears to provide us a useful baseload when the sun isn’t shining, or the wind isn’t blowing.

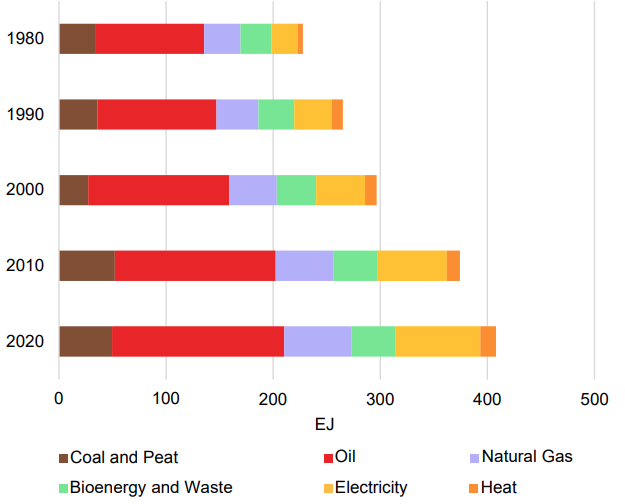

According to Cameco, one of the world’s largest uranium producers, global power demand is expected to grow 75% by 2050. Nuclear power’s role in this growth will be supported by over 50 new reactors currently under construction, with China, Russia, and India leading the charge in terms of building new capacity. According to Paladin Energy, Australia’s largest listed uranium pure-play, China’s longer-term plans are to build as many as 150 new reactors over the next decade alone. Reactors currently under construction, and those planned, will complement the existing stock of approximately 450 working reactors spread across 32 countries. To put the current contribution of nuclear power into perspective, it provides approximately 10% of the world’s electricity demand, a mere fraction of the approximately 40% (and growing) currently supplied by coal-fired generation. One would think this ratio needs to change significantly if countries are to meet their recently announced 2050 carbon-neutrality targets.

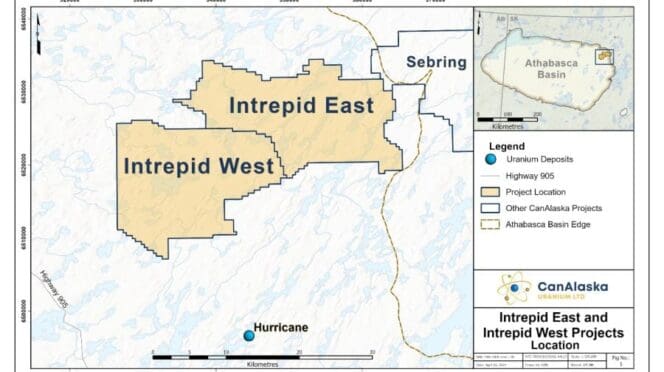

World Final Energy Consumption by Energy Source (Source: International Atomic Energy Agency, “Energy, Electricity and Nuclear Power Estimates for the Period up to 2050”, 2021)

According to the World Nuclear Association (WNA), the world’s current nuclear reactors require 74,000 tonnes of U3O8 (uranium oxide) each year. This supply is met from mines, running down stockpiles, or via secondary sources (we’ll discuss these later). Whilst there are many nuclear reactors under construction, due to the long lead times in bringing one online, capacity is growing slowly. Further, existing nuclear reactors are regularly being made more efficient (this has resulted in roughly a 25% decrease in uranium consumption within the industry since the 1970’s). It’s also worth noting nuclear power requires substantial up front capital investment, and nuclear power’s fuel requirements are relatively predictable compared to the demand for your typical industrial metals. Putting all these demand-side factors together, they suggest nuclear power generation is unlikely to cause a rapid and substantial demand-side shock within the uranium market any time soon.

Still, demand is expected to grow steadily over the medium term. The WNA predicts a 27% increase between 2021-30 versus a 16% increase in nuclear reactor capacity (the decline is explained by the difference in demand for material contributing to new cores versus simply replacing spent material from old cores down the track). As more new nuclear reactors are brought online, the longer-term growth rate (between 2031-40) is expected to be closer to 38%.

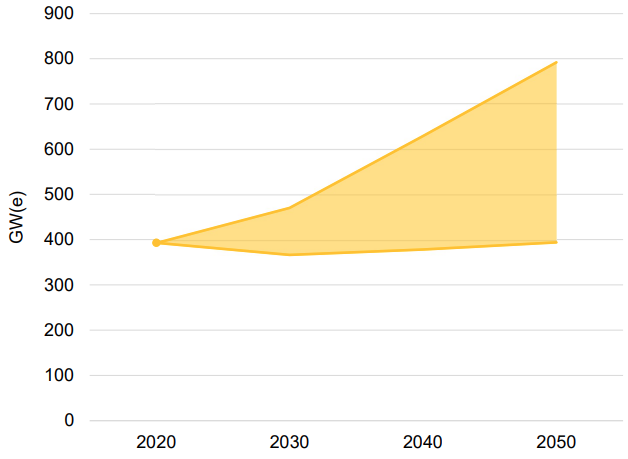

Alternatively, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) provides two main scenarios for nuclear reactor demand. A “high case” where nuclear reactor capacity increases 20% by 2030, 60% by 2040, and 101% by 2050; and a “low case” where nuclear reactor capacity decreases 6% by 2030, 4% by 2040, and increases to be flat with current capacity by 2050. Clearly, the uranium price is going to move very differently under the WNA base and IAEA high case scenarios, compared to the IAEA’s low case scenario. (FYI, IAEA’s low case assumes around one quarter of existing plants are retired by 2030, but between 2030 and 2050 capacity additions from new reactors will slightly exceed requirements).

World Nuclear Electrical Generating Capacity High Case & Low Case (Source: International Atomic Energy Agency, “Energy, Electricity and Nuclear Power Estimates for the Period up to 2050”, 2021)

Uranium market supply side

Whilst the demand picture is fairly clear for the next few decades, supply factors impacting the uranium market are notoriously dynamic. For example, the Fukushima nuclear power plant incident in 2011 caused the immediate shutdown 46 out of 50 of Japan’s reactors (just 9 have since resumed operation). Fukushima also had wider ramifications for sentiment towards nuclear energy in Europe, for example, since 2011 Germany has shut down 11 out of 17 of its nuclear power plants and Belgium is aiming to exit nuclear power generation by 2025. Other countries also announced less sweeping shutdowns and also scrapped plans to build new reactors.

This sounds like a discussion about the demand side, correct? Well, it is arguable the Fukushima incident triggered a major decline in uranium prices over the remainder of the decade (see chart below). The uranium price fell from around US$70 per pound in 2011 just before the Fukushima incident to just under US$18 per pound near the end of 2017.

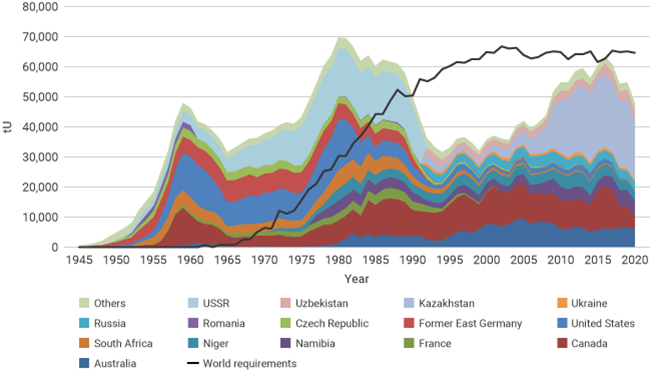

The impact of this price plunge on global uranium production was substantial. It caused a large number of mining operations to become uneconomic, that is, their cost of production exceeded their realised sale price. As a result, a number of producers chose to cease production, putting their mines on care and maintenance in the hope of restarting should the uranium price eventually improve. According to the WNA, global uranium production declined by approximately one-quarter between 2016 and 2020. This decline can be seen clearly on the chart below of long-term uranium production versus world demand, taken from WNA.

Historic Uranium Supply by Country (Sources: OECD-NEA/IAEA, World Nuclear Association The Nuclear Fuel Report)

The other item evident on the chart, is due to the decline in supply over the latter half of the last decade, demand for uranium now exceeds its production by approximately 16,000 pounds. The imbalance is presently being supplied by inventory drawdowns by nuclear power operators and via the down-blending of material from nuclear weapons.

In the chart below, we can see since 2020 global production has eased further, albeit only slightly, due to impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s also worth mentioning that since 2016, a number of maintenance issues, accidents, and weather events have also negatively impacted production. These are ongoing issues regularly impacting any mining-related industry, but they do have the ability to substantially swing supply in the uranium market on a short-term basis.

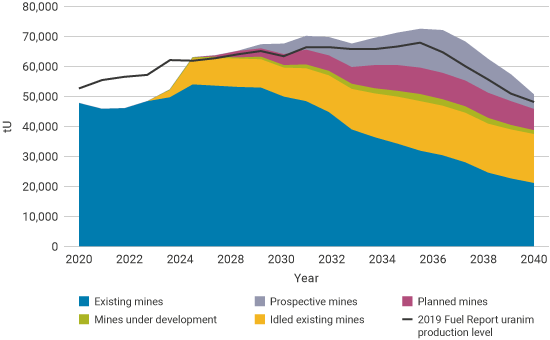

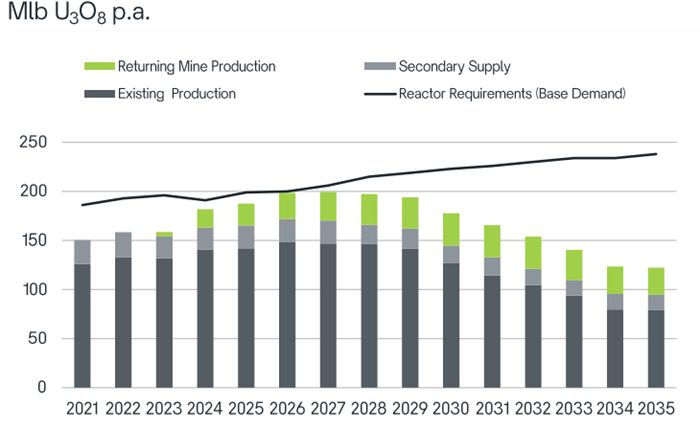

Long Term Uranium Supply Forecast (Source: The Nuclear Fuel Report, World Nuclear Association)

Looking forward, there are two major factors likely to impact the global supply of uranium. The WNA expects production to increase over the next decade as pandemic impacts subside, allowing those producers who are economically viable at the current uranium price to increase their supply. Note however, how the supply from what they call “Existing mines” is expected to fall away sharply towards the end of this decade. Fact: mines eventually run out of resources if those resources are not replenished by investment in exploration and development. Very low-cost producers such as Kazakhstan’s Kazatomprom (approx. 21% of global production) and Canada’s Cameco (approximately 17% of global production) will no doubt each play a major role in delivering on this supply increase.

For those producers who are not currently economically viable, their potential supply (i.e., what WNA calls “Idled existing mines”) is contingent on a sufficient recovery in the uranium price. Industry experts widely point to a uranium price sustainably greater than US$50-$60 per pound as the tipping point to enable the restart of mothballed supply. The word “sustainably” is important here. In April, we saw the uranium price tickle $US60 per pound for a couple of weeks. As we kick off May, recent concerns about Chinese economic growth have triggered a pullback in to the low US$50’s. It’s difficult for uranium companies sitting on mothballed supply to make crucial long-term investing decisions based upon such short-term volatility.

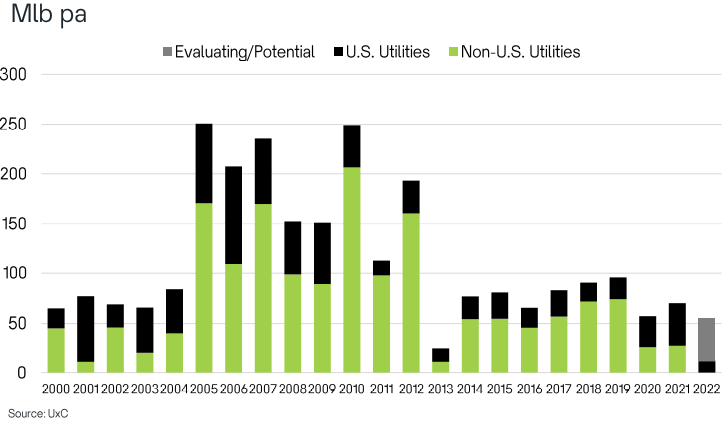

Spot prices get a great deal of attention, but in the medium-to-long term, long-term contracts between producers and nuclear power utilities account for the bulk of uranium sales. Around 85-90% in fact. So, for the next uranium bull market to begin, we’ll need to see these contracts begin to be consistently set above the US$60 per pound mark. Utilities companies tend to wade in only after the spot price is showing signs of getting away from them, that is, a little FOMO is required! Given the recent pullback in the spot price, we’re probably not quite there yet.

Nuclear Power Utilities “Historic Term Contract Activity” (Source: Paladin Energy Investor Presentation February 2022)

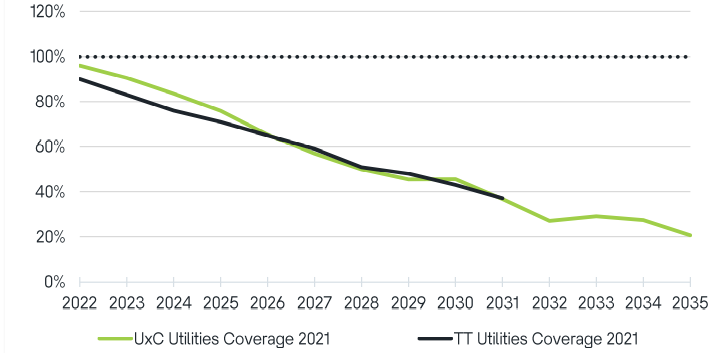

However, spot price gyrations aside, the charts above and below demonstrate global nuclear power utilities are potentially getting a little twitchy. We can see from the Historic Term Contract Activity chart above, since Fukushima, utilities have been content to draw down on stockpiles and utilise secondary sources for supply. But it appears nearly a decade of low term contracting has left them increasingly exposed with respect to covering their requirements going forward. Looking at the Global Contracted Coverage of Base Requirements ratio in the chart below, it appears nuclear power utilities are potentially just moving into deficit. Their collective rate of coverage steadily declines to around 45% by the end of the decade, and to as low as 20% by 2035.

Global Contracted Coverage % of base requirements (Source: Paladin Energy Investor Presentation February 2022)

As is commonly the case with the uranium market, there’s usually about 100 different factors pushing and pulling in opposite directions. Due to the nature of their business (which is ultimately the reliable supply of electricity), nuclear power utilities tend to be very fussy with who they do business with. This means they must be assured of supply and safe transport of what is a notoriously hazardous material. Supply chains and transport costs are under extreme pressure at the moment due to the pandemic, and more recently, the war in Ukraine. Frustratingly for uranium bulls, they may have to wait for these issues to be resolved before we see any major pick up in long-term contracting activity. (Just on the war on Ukraine, it is possible the EU bans imports of Russian uranium which would knock out a significant portion of supply to the region – which will need to be made up elsewhere…talk about push and pull!).

Longer term, the supply of uranium is expected to decline as a result of underinvestment in new production capacity and exploration to identify new resources. WNA estimates investment in uranium exploration has fallen by nearly 80% since the middle of the last decade. This is typical of any commodity which has experienced a prolonged downturn in price, and a similar situation also occurred recently in the lithium industry to constrain supply there. Another factor limiting new uranium supply is the negative stigma associated with nuclear power due to disasters such as Chernobyl and Fukushima, and due to the problem of storing hazardous spent nuclear waste. This means investing in uranium projects is rarely very high up on the ‘to do’ list for ESG-conscious investors, and this has and will continue to limit industry’s ability to fund new and expanded production.

Structural Supply Shortage, TradeTech (Source: Paladin Energy Investor Presentation February 2022)

The chart above ties together the long-term supply picture with the long-term demand picture. It does appear unless we see a major ramp up in investment in exploration and/or increasing productive capacity at existing operations in the very near future, the uranium market is going to begin to increasingly move into deficit around the start of the next decade.

Prices down. Production down. Deficit looming. Enter Sprott!

Just after the pandemic, the uranium price was dragging itself off the canvas. COVID-19 was beginning to wreak havoc with mine production and the industry was on its knees after half-a-decade of underinvestment. The global energy picture was changing rapidly as major governments almost unanimously tilted towards the goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. Nuclear power utilities were slowly but surely drawing down on their stockpiles in the wake of Fukushima.

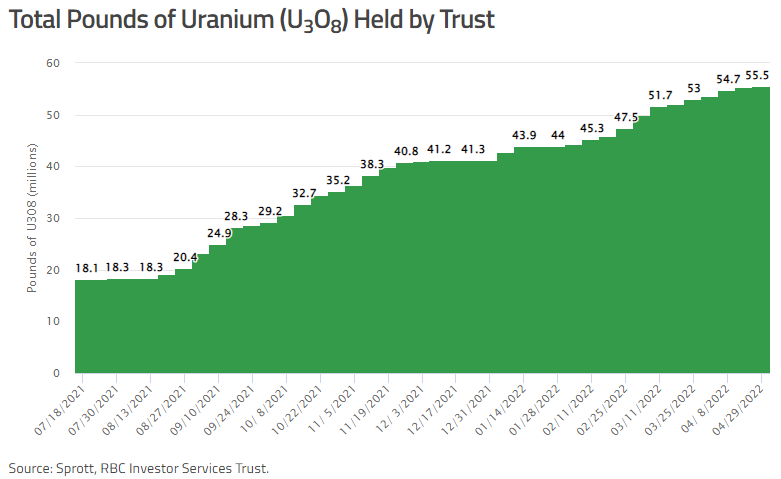

Enter Toronto based Sprott, a precious metals focussed global asset manager named after founder Eric Sprott. In July 2021, Sprott expanded its portfolio of exchange traded physical trusts, each aimed at providing investors direct access to a precious metal such as gold and silver, to also include uranium. The Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (SPUT) began buying and storing uranium on the spot market to back investors’ investments. It now holds over 55 million pounds of U3O8 in trust for investors with a market value of nearly US$3 billion dollars.

Sprott Physical Uranium Trust historical fund holdings (Source: Sprott)

The advent of SPUT has been a positive for the uranium price with the trust’s purchases adding to existing demand. It has bolstered investor confidence, swinging sentiment back to the bull side in a market which was desperately in need of a spark. Sprott has publicly stated it intends to be a long-term holder in the market, and it has no intention of selling its current holdings to other entities. If this is the case, Sprott just took a significant whack of supply out of the market indefinitely. Further, as can be seen in the chart above, their uranium purchases continue unabated. The trajectory of this chart will no doubt be closely monitored by market participants.

Uranium price outlook

It is clear the supply side of the uranium market is presently awaiting price improvement before ramping up production/returning to production. Balanced against this is the slow and predictable build up in demand from nuclear power utilities which does appear to be very real, and the prospect of their scaling up their term contracting in the near future. Then, throw in the curveball which is Sprott. So, is this an environment where prices are more likely to rise, fall, or stay where they are?

We started this discussion with the question of whether uranium can be the “next lithium”. Without going into the detailed dynamics of that market, it is fair to say the demand for lithium is experiencing a less predictable and a more explosive increase compared to the demand for uranium currently is. This would suggest a similar explosion in the uranium price, which has indeed occurred in the prices for many lithium minerals, is less likely.

Still, the underlying dynamics within the uranium market of increasing demand, in an environment where in the longer term at least, supply is likely to decrease, does lend itself to long term price appreciation. As always, in any market however, timing is everything – and the timing of a considerable (lithium-style) deficit in the uranium market is potentially as much as a decade away. Now, this doesn’t mean we can’t see the recent uptrend in the uranium price continue as geopolitical factors and supply chain disruptions do their bit to bolster the short-term bull case. Also, improving sentiment and increasing awareness (e.g., via articles like this!) can do wonders for any market. It does appear from the uranium chart both sentiment and price trend has turned. Indeed, if the uranium price can remain above US$60 per pound for more than a couple of weeks (read as a couple of quarters), I expect it will light a fire under many of the local uranium plays we’re going to investigate in Part 2. Stay tuned!

Original Post Here