Table of Contents Show

Will It Cut Carbon or Curb Production? • Carbon Credits

Canada’s upcoming emissions cap on the oil and gas sector aims to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 37% by 2030 from 2022 levels. However, the energy industry and provinces like Alberta are strongly opposing it.

The plan, unveiled Monday, introduces a cap-and-trade system designed to encourage higher-polluting firms to invest in emissions-reduction projects while recognizing better-performing companies. The intent to cap the oil and gas industry was first revealed during the COP28 last year in Dubai.

Beyond Black Gold: A Green Transition?

Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault clearly emphasized the importance of this move, stating that:

“Every sector of the economy in Canada should be doing its fair share when it comes to limiting our country’s greenhouse gas pollution, and that includes the oil and gas sector. We are asking oil and gas companies who have made record profits in recent years to reinvest some of that money into technology that will reduce pollution in the oil and gas sector and create jobs for Canadian workers and businesses. ”

Canada’s oil and gas sector contributed 31% of the country’s total emissions in 2022, per the latest National Inventory Report. It is the largest emitting sector, followed by the transportation and buildings sectors.

High Stakes in the Oil Sands

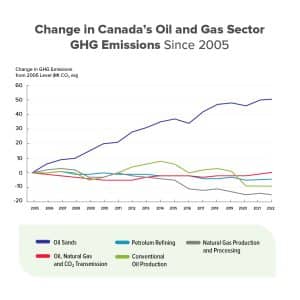

In 2022, Canada’s oil sands led to oil and gas emissions of 87 megatonnes or 40% of the sector’s total. The sector’s emissions have largely been driven by increased production.

Since 1990, Canada’s total crude oil output surged by 193%, primarily fueled by oil sand operations, which grew over 800% and accounted for 80% of this production increase. This growth underscores the oil sands’ significant impact on Canada’s total emissions.

Source: National Inventory Report

Source: National Inventory Report

These major carbon emitters are largely concentrated in the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, where oil sands and natural gas production are prevalent. Here are a few key players, with their latest GHG emissions reported and net zero goals.

Suncor Energy Inc.

One of Canada’s largest integrated energy companies, Suncor operates in Alberta’s oil sands, where its extraction and processing activities generate significant emissions. The oil major’s GHG emissions totaled almost 35 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO₂e) in 2022.

Suncor aims to achieve net zero in its operations by 2050 and cut emissions by 10 megatonnes across the value chain by 2030. The company has been actively pursuing emissions reduction initiatives, including investments in carbon capture and renewable energy.

Canadian Natural Resources Limited (CNRL)

CNRL is among Canada’s top oil sands producers and one of the largest carbon emitters in the country, releasing over 23 million MtCO₂e in 2022. They are a key member of the Pathways Alliance, along with Suncor, which aims to build carbon capture and storage (CCS) networks to reduce sector emissions.

The energy firm commits to reducing its carbon footprint by 40% in Scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions by 2035m compared with the 2020 baseline. It also targets to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Imperial Oil Limited

A major player in the oil sands and petrochemical industries, Imperial Oil operates facilities with large carbon footprints, including open-pit mining and in-situ extraction operations. It has also partnered with CCS initiatives to cut emissions.

The oil major aims to hit net-zero scope 1 and 2 emissions, from operated assets by 2050. Its emissions totaled 8.9 million MtCO₂e in 2021.

Cenovus Energy Inc.

Known for its oil sands and conventional oil operations, Cenovus has significant emissions, especially from its steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) operations. Cenovus is also part of the Pathways Alliance, focusing on long-term decarbonization.

The company aims to slash GHG emissions to net zero by 2050, with 18.2 million MtCO₂e produced in 2022.

How Canada’s Emissions Cap Could Redefine Oil & Gas

Canada’s proposed emissions cap for the sector focuses on emissions rather than limiting production. These regulations are informed by discussions with industry, Indigenous communities, provinces, territories, and other stakeholders and are designed to align with achievable technical measures, per the government’s statement. This approach allows for production growth, with Environment and Climate Change Canada projecting a 16% production increase by 2030-2032 from 2019 levels, assuming companies implement decarbonization measures.

The pollution cap will regulate upstream oil and gas facilities—including offshore and liquefied natural gas (LNG) production—which account for roughly 85% of the sector’s emissions. Activities covered include:

oil sands extraction and upgrading,

conventional oil production, natural gas processing, and

LNG production.

As the world’s 4th-largest oil and 5th-largest gas producer, Canada aims to stay competitive in a decarbonizing global market. With demand for low-pollution fuels expected to grow, the emissions cap is positioned to help Canadian oil and gas producers adapt to shifting global demand while supporting national emissions targets.

As Canada targets a 40-45% emissions reduction below 2005 levels by 2030, it’s clear that the energy sector, which accounts for over a quarter of all emissions, is key to achieving its climate goal.

Tug of War Over Emissions Limits

The cap on emissions, however, is being criticized by Alberta and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), who argue it’s essentially a production cap. They contend the policy could drive up prices, eliminate up to 150,000 jobs, and cost Canada’s economy up to C$1 trillion (US$720 billion).

Alberta’s opposition reflects broader industry concerns that Canada could become the only major oil and gas-producing country capping emissions. They noted that this could potentially harm the nation’s competitiveness.

Greenpeace Canada’s Keith Stewart expressed that oil companies haven’t invested enough in pollution-reducing measures, underscoring the need for a strict cap. Conversely, Deloitte’s June analysis suggests that the cap may drive companies to cut production rather than adopt costly technologies like CCS, a solution proposed by some as a way to curb emissions without reducing output.

As the debate intensifies, it highlights the tension between ambitious climate policies and economic impacts on the energy sector and provincial economies. The final plan and its reception will be pivotal in shaping Canada’s climate and energy future.